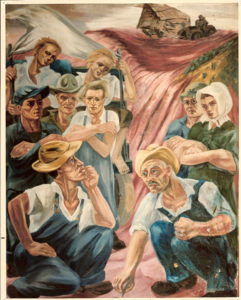

My friend Bernard was the lead artist on the famous Coit Tower mural project. Back in the early eighties I took him to the reopening ceremony (the tower had been closed for much needed renovation, and it needs renovation again). A few of the original artists were there, and it was a thrill for me to meet those living legends, and to see the great respect they still displayed for their old comrade. If you have six minutes, the video “Zakheim: The Art of Prophetic Justice” is quite good. Near the end it shows his son and grandson discovering a fresco that was painted over decades ago. Seeing it come back to life, it’s as if Bernard is speaking to them, and to us, from across the decades

I had not heard the term Ekphrasis “. . .a vivid, often dramatic, verbal description of a visual work of art . . .” when I wrote the piece that follows. On a carbon copy of the long-forgotten manuscript — yes, we used carbon in those days — my hand written inscription to Bernard had transferred through; there for me to discover all these years later, just like Barnard’s lost mural

You painted from their suffering

I wrote from your painting

Our work will help them remember.

Ed

Tractored Out

By Ed Davis

One man is down on his haunches drawing with a stick in the dust.

One man is down on his haunches drawing with a stick in the dust.The heads of the households, the men and women of the families, are accustomed to tough times.

Deceptively simple, they may have little education, yet can foretell the future in a bank of storm clouds and recount the past from the ground at their feet.

Such people write their stories, not with paper and pen, but on the face of the land with plows and sweat and love. Put them in the city, on the street corner or in the breadline, and you turn them into bums. Leave them in the country with their toil and their pride, and you leave them with hope, however thin, however brittle.

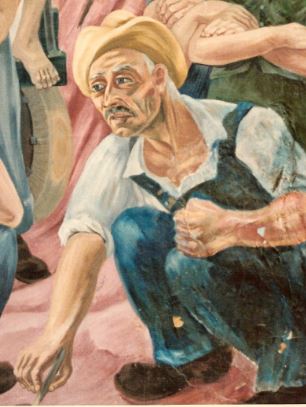

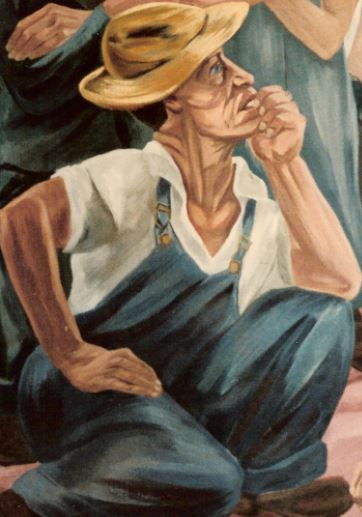

Look at the crouching man — his shapeless hat, the deep sunburn of his face, the knotted muscles of his hands — and you see only the ravages of his arduous life. You see the losses his body has suffered through the years. A finger or an arm taken by the harvesting machine. An eye gone milky from a chipped splitting maul. Or thinning hair and a nervous twitch from too much work, or too much worry, or just too much.

Look at the crouching man — his shapeless hat, the deep sunburn of his face, the knotted muscles of his hands — and you see only the ravages of his arduous life. You see the losses his body has suffered through the years. A finger or an arm taken by the harvesting machine. An eye gone milky from a chipped splitting maul. Or thinning hair and a nervous twitch from too much work, or too much worry, or just too much.

You see the man’s losses at a glance. What you don’t see are his victories.

What you don’t see is his incredible strength.

He draws a windmill and a water tank, then wipes them away with his hand.

How strong must a man be to remain silent as he feels the freshness and vitality of his youth seep slowly into the stony ground that he works sixteen hours a day? What strength must a man have to watch the woman he loves, who struggles tirelessly at his side, give up her beauty to the wind and the sun and the work of a life whose only rest is in sleep, and whose only sleep is in exhaustion?

How strong must a man be to remain silent as he feels the freshness and vitality of his youth seep slowly into the stony ground that he works sixteen hours a day? What strength must a man have to watch the woman he loves, who struggles tirelessly at his side, give up her beauty to the wind and the sun and the work of a life whose only rest is in sleep, and whose only sleep is in exhaustion?

How strong must they be, even in their hunger, to always feed their family members first, leaving little or nothing for themselves? They must make every decision and be right every time, must have an answer for every question yet be answerable only to each other. Their joys and sorrows will never be known, for to exalt in gladness or cry in despair would expose a vulnerability they can never dare to show. To their children, to their parents, and for themselves they must be the masters of the world. They alone hold the reins, they alone fight the desperate battles, and it is the two of them who must win each day for all.  Such a burden would bow the back and break the spirit of many a scholar or captain of industry, but these simple people of the soil carry the load without complaint, and their strength seems to have no limit.

Such a burden would bow the back and break the spirit of many a scholar or captain of industry, but these simple people of the soil carry the load without complaint, and their strength seems to have no limit.

The man draws a barn and a house and a fence, then wipes them away too.

There is a limit. For thousands it was reached when they stood face-to-face in their pastures and at their doorsteps with a monstrous, smoke-belching earth mover. Had it just been a tractor, just a machine with pistons and pulleys, they could have beaten it. Even if it were a fleet of tractors these resolute people with their minds and their hands could have won out. But the machine they faced was more powerful than any bulldozer, more powerful in fact than any other invention of man. The machine they faced was progress, and it was impossible to stop. For an engine it used greed, for controls it used the laws of the land, and for fuel it burned money. It had one speed; relentless. One direction; forward. One goal; profit.

Even so awesome an enemy might have been resisted had it not been for one thing —people drove the tractors that were demolishing the dreams of a generation. Not monsters, not demons, but ordinary people who wore goggles and masks to hide their shame. When the farmers would attack one of these drivers, drag him from his machine and rip his mask away, the eyes that looked up at them in anguish were familiar eyes, and the frightened face was one of their own.

Even so awesome an enemy might have been resisted had it not been for one thing —people drove the tractors that were demolishing the dreams of a generation. Not monsters, not demons, but ordinary people who wore goggles and masks to hide their shame. When the farmers would attack one of these drivers, drag him from his machine and rip his mask away, the eyes that looked up at them in anguish were familiar eyes, and the frightened face was one of their own.

Most farmers lost their homes and were forced to move.

Some farmers lost their pride and were forced to drive tractors.

These proud, valiant people of the land might have fought a machine called progress and won, but they could not fight themselves, and thus, their spirit was broken.

On the smooth sandy place before him, the man draws the words “Our Land”

All of his concentration goes into forming the words. He pays no heed to the tractor approaching pitilessly over the hill.

When he finishes he stands, on legs already weary from a lifetime of work, and begins walking slowly toward town, forever turning his back on his home, and his history, and everything that has come before. With the mirror of his past shattered, its images wiped away, he can no longer see any reflection of himself in the future.

The tractor advances methodically.

The tractor advances methodically.

It rolls over the spot where the farmers had gathered.

It rolls over “Our Land.”

And it rolls on.

The End

A beautiful piece along side a beautiful painting. I think Bernard would be happy to see these two works together for more people to enjoy.

“Ekphrasis” indeed. You have moved me to tears remembering those who are still being tractored out.

If you want to use the photo it would also be good to check with the artist beforehand in case it is subject to copyright. Best wishes. Aaren Reggis Sela

Right you are. I cleared this with Bernard’s estate before posting. Thanks!

Beautifully put; it captures all that only one can see if they have been there themself. I choked up half way thru and had to read the rest thru teary eyes.

Thanks!